- CMSD Media Center

- Latest

CARE theater program helps students explore emotions (Video, photo gallery)

CMSD NEWS BUREAU

11/7/2017

For Bolton School eighth-grader Kierra, her weekly theater class is what she calls “a safe space.”

It’s no accident that Kierra feels this way. Creating a safe environment is one of the main goals of CARE (Compassionate Arts Remaking Education), a Cleveland Play House program that uses theater to help CMSD students feel safe at school, identify and process their emotions in healthy ways and improve literacy.

“Normally, a scholar is expected to sit in their desk,” said Thomas Kazmierczak, CARE project manager for the Cleveland Play House. “Here, they’re active, they participate, they feel safe and they contribute greatly to our classrooms. It’s all lessons about feelings, emotions and getting along safely -- all through theater.”

Full-time teaching artists are working in four District schools - Bolton, Marion-Sterling, Alfred A. Benesch and Robert H. Jamison. The program kicked off at the beginning of the the 2015-16 school year after the Cleveland Play House received a U.S. Department of Education grant.

Since then, the teaching artists have been meeting once a week with each class in those four schools, teaching students not only how to act, but how to confront their emotions. So far, the results are promising, showing improvements in the surveyed areas of social and emotional competence, theater education and English language arts.

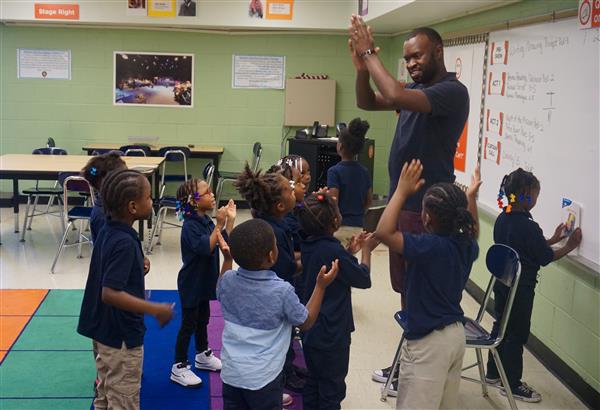

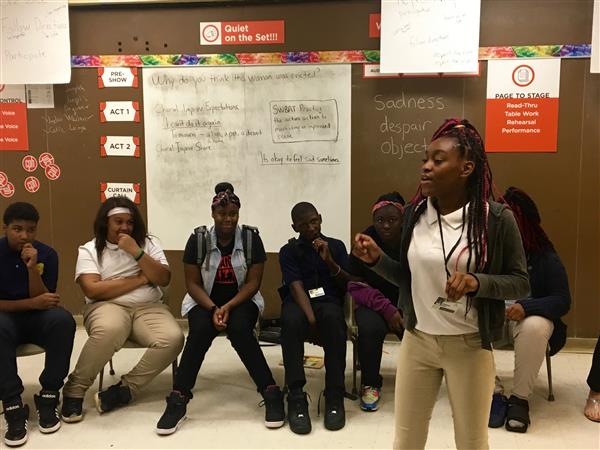

The classes are less about sitting and talking and more about moving and expressing creativity.

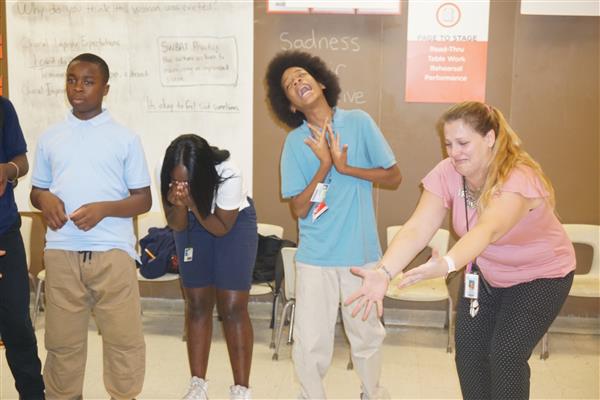

A typical class for Bolton eighth-graders looks something like this: The students file into a classroom and sit in chairs that are arranged in a circle. Posted on each wall are stage directions: Stage Right, Stage Left, Upstage and Downstage. Signs around the room read: Curtain Call, Audience Voice, Backstage Voice and other theater terms for the teachers to point to during lessons.

Students begin the class by watching a video. It’s one of 32 monologues that CPH commissioned 16 playwrights to create for the CARE curriculum, developed specifically with CMSD students in mind. The “culturally responsive” monologues explore a wide range of emotions using topics that may resonate with urban children.

A monologue that the Bolton eighth-graders watched was about a woman who was evicted from her apartment. The actress described seeing all her belongings splayed out by the curb and wondered how she could bring herself to go through the process of finding somewhere smaller and cheaper to live.

After the video ended, Abraham Adams, the Bolton CARE teacher, introduced the emotion the class would be exploring that day: mourning.

“In that monologue, the woman was mourning the loss of her house,” Adams told the class. “I want us to come up with a made-up scenario where we’re dealing with the idea of mourning.”

Immediately, ideas burst from the students’ mouths and a narrative began to form: A family’s beloved Chihuahua named Peanut Brittle had been struck by a bus and died. Soon, the students began acting out the characters at the dog’s memorial service: a band, a choir, the owners and, yes, the deceased dog.

Adams said this activity and others like it aren’t just a fun way to get students out of their seats, they also help students recognize certain emotions in themselves and in other people.

“This program isn’t designed to create the next acting phenomenon,” Adams said. “We teach skills that are often referred to as soft skills, but these skills are necessary. Theater is a great vehicle for that.”

To monitor the effectiveness of CARE, the Play House enlisted an independent company, Philliber Research and Evaluation. The researchers compared the four CARE sites with four other CMSD schools with similar demographics.

The results showed that none of the students demonstrated the ability to generate and conceptualize artistic ideas and work in fall 2015; this rose to 59 percent by spring 2017.

In the English language arts area, CARE students in grades 5-8 averaged a 6 percent higher reading level percentile than those at the control schools; and CARE students in that grade band had a 7 percent higher reading proficiency rate than control students.

Additionally, 52 percent of CARE students reported feelings of schoolwide safety compared with 32 percent of control students.

The researchers saw the most significant difference in male students. Teaching artists ventured several possible explanations for this success, including that the curriculum features many male writers and often uses male protagonists or portrays a male in a vulnerable emotional state.

A Bolton eighth-grader named Jasuam said he likes his weekly theater class with Adams because it incorporates movement and teaches him how to act.

“He taught me more about acting, and I got better throughout the years,” Jasuam said. “We get to do more stuff than other classes. We get to talk more and walk around more.”

Kazmierczak said the curriculum is also designed to help students deal with trauma related to growing up around poverty, violence and other challenges. Part of this is helping students feel less isolated through activities that let them know their classmates are going through some of the same things.

Both Kierra and Jasuam said one of their favorite parts of CARE is a game called “The Wind Blows West,” a musical chairs-style game where students take turns saying a statement that is true for them. If that statement is true for any other students, those students must stand up and switch to a different chair. It can delve into light topics like, “I have a younger sister” and heavier ones like, “I have a parent in jail.”

“It builds community, it builds empowerment and it lets them know they’re not alone,” Kazmierczak said.

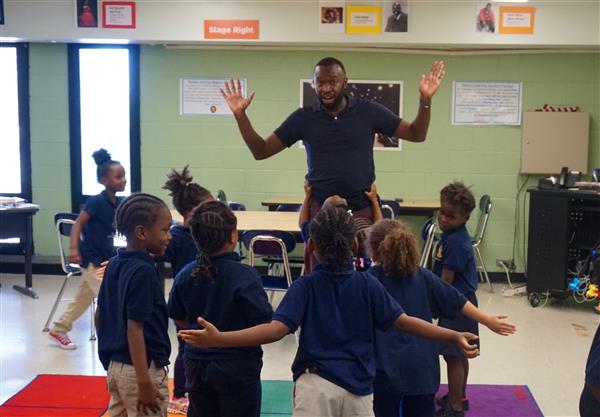

CARE looks much different for younger students, but the mission of stirring up creativity and helping students face their emotions is the same.

Eugene Sumlin, the teaching artist at Marion-Sterling, sometimes begins his kindergarten class using iPads that CARE supplies for his classroom.

The team that developed CARE came up with four iPad applications related to the curriculum. One of the apps, Emotion Match, puts a twist on traditional memory games. Unlike most matching games, which rely on memorization, Emotion Match presents a variety of faces at the same time and the user matches the emotion portrayed by the faces across gender and race.

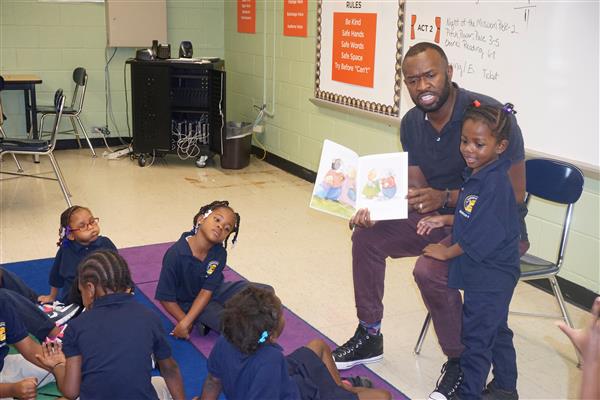

Getting younger children interested in theater can be difficult, so Sumlin uses storytelling as a gateway.

“The entry point is that theater is communicating a story with your voice and your body,” he said.

One of Sumlin’s classroom activities involves reading a short book to the class and then talking about how the characters felt at certain points in the story. Later, he asks each child to give an example of a time they made someone else sad and how it made them feel. They have the option to hug a teddy bear in the classroom after they come forward.

"With the younger kids, the thing I work on most is letting them know that this is a safe environment," Sumlin said. "When they come in here, they're free to express themselves and they can be who they want to be."

Kazmierczak said CARE isn’t designed to be a cure-all for students with emotional or behavioral issues, but rather an opportunity to use the therapeutic quality of theater to help children cope with common emotions. Teaching artists each receive 16 hours of professional development in trauma-informed care from a drama therapist so they know how work with children who have been traumatized, respond when traumatic material surfaces and understand how to create the kind of "safe space" that Kierra said she feels in her classroom.

“If you go see a show, you begin to express your emotions and you can identify with the characters on stage," Kazmierczak said. “That’s what we do in our classrooms. We help them identify, through theater, all those emotions that will help carry them through.”